First published by the Local Schools Network, September 2016

‘We don’t mind being compared to McDonald’s’

Per Ledin, CEO of Kunskapsskolan

Selling schools like groceries

Milton Friedman in the 1970s

Milton Friedman in the 1970s

In the autumn of 1973, an article by Milton Friedman appeared in the New York Times. Entitled ‘Selling Schools like Groceries’, the piece was part of Friedman’s long campaign to revolutionise public education by means of a voucher system. The 52-year-old economist, about to come into his own as a guru of the New Right, outlined a future in which traditional public schools would be replaced by ‘highly capitalised chain schools’, run ‘like supermarkets’ by profit-making companies.

In the 1990s, as the market-driven reform of public education gathered pace in the USA, such companies did indeed begin to emerge. One was Edison Schools Inc., which now – as EdisonLearning – runs a number of English academies. Other US firms, like K12 Inc. and Mosaica, have also acquired schools here, as has the Dubai-based GEMS Education.

Of course, these firms are not yet able to profit directly from running English state schools. And it has to be said that, back in the USA, for-profit companies have proved less effective operators of public schools than non-profit ‘charter management organisations’ like KIPP (the Knowledge is Power Programme), which now has a chain of 200 schools across 20 states. Backed by philanthropic businessmen and financiers, non-profit entities like KIPP – or Ark Schools, its English twin – can explore ways of running schools on business lines, without pressure from investors looking for quick returns.

However, there is one for-profit company which has come close to realising Friedman’s vision of a fully marketised and commercialised education system. This is Kunskapsskolan, described by its founder as ‘one of Sweden’s five largest school chain companies’. Kunskapsskolan’s attempt to break into the English schools market was not a success, as we will see. But the model developed by the company – highly cost-efficient, technology-driven, and skilfully marketed – is proving very influential, both in the USA and here.

The background: market experiments in the People’s Home

In 1991, Sweden’s Social Democratic Party lost power to a right-wing coalition. The new government launched a radical programme of public sector reforms, which included significant deregulation of the schools system. Sweden became the first country since Chile under General Pinochet to try out Milton Friedman’s voucher plan – or a version of it – on a national scale. As Anders Hultin, a young special adviser who played a key role in implementing the reforms, recalled in 2009: ‘our proposal was fairly simple: anyone could set up a school, and be paid the same per pupil as state institutions’.

Anders Hultin: ‘”profit” is not a dirty word’

The consequences were predictable: (1) the rapid commodification of public education, with the majority of the new ‘free schools’ being run by profit-making companies; (2) a sharp rise in the activity of private equity firms within this new sector, as the vultures fought over the public funds suddenly made available for private gain.

In 2013, one of the new school businesses, JB Education, got into financial difficulties. Its owner, the Danish private equity firm Axcel, walked away, and the chain collapsed. Around 10,000 students were enrolled in the company’s schools. Commenting on the fiasco, Ibrahim Baylan, the Social Democrat schools minister between 2004 and 2006, told the Guardian: ‘Nobody could foresee that so many private equity companies would be in our school system as we have today’.

Emilsson and company: PR, politics, and schools

Kunskapsskolan (the ‘Knowledge School’) was founded in 1999 by Peje Emilsson, a ‘politician, entrepreneur and consultant in strategic communications’. Emilsson’s first enterprise, back in 1970, was a PR firm called Kreab, which later merged with a US company to become Kreab Gavin Anderson. In 1989, Emilsson started Demoskop, a marketing firm. The next step, following the shock therapy administered to Swedish society by the 1991-94 government, was a move into privatised public services: schools (Kunskapsskolan) and care homes (Silver Life, a ‘chain that provides security, service, and comfort’).

Peje Emilsson has excellent political connections. Carl Bildt, the leader of the 1991-94 administration, was on the board of the Magnora Group, the Emilsson family’s holding company. And a number of Bildt’s colleagues in the coalition government were involved in the creation of Kunskapsskolan.

Per Unckel, minister of education in the 1991-94 government, sat on the company’s board.

Anders Hultin, the young architect of the school reforms, was Kunskapsskolan’s co-founder and first CEO. (He went on to work for GEMS Education and Pearson, and then became head of JB Education shortly before the company’s collapse.)

Odd Eiken, another former schools minister, was until recently CEO of Kedtech, Kunskapsskolan’s subsidiary ‘for development of educational technology and services in emerging economies’. Like Emilsson, Eiken started out as a PR man.

Odd Eiken in Bahrain in 2015; as CEO of Kedtech, he sold ‘educational technology and services’ in emerging markets

Emilsson, Hultins and Eiken are entrepreneurs who move easily between the worlds of business, PR, and politics. They present themselves as faithful disciples of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman. Emilsson describes the marketisation and privatisation of Swedish schools as a ‘freedom explosion’. Running schools (or care homes) for profit is a blow against ‘a monolithic state system providing few choices’. For Odd Eiken, choice is the ‘market mechanism’ which will allow ‘the private capital market and private enterprise to contribute to […] educating the next generation’.

Anders Hultin is another free market missionary. In 2009, he used an article in the Spectator to lecture Cameron’s Conservatives on the virtues of choice, competition and the profit motive:

There is indeed a schools revolution waiting to come to Britain, but one that can only reach its potential if the Conservatives realise that ‘profit’ is not a dirty word.

‘A better result at 20 per cent lower cost’

In 2011, Peje Emilsson visited Washington D.C., where he gave a talk at the Cato Institute, the libertarian think tank founded by Charles Koch in the early seventies. Emilsson explained the anti-government, free market philosophy behind Kunskapsskolan: ‘those who believe that you cannot make education more efficient are just wrong […] anything the government does, you can of course get a better result at 20 per cent lower cost’.

Efficiency — in other words, control of costs — is the guiding principle of Kunskapsskolan’s business model. The basic features of the model are common to other for-profit education providers:

- consolidation of ‘back office’ functions (Emilsson: ‘one corporate back office which handles all support operations such as marketing, administration, financial and human resources’)

- an increased student-teacher ratio

- performance-related pay

- a proprietary curriculum, used by all schools in the chain, and licensed to other school operators

- a heavy reliance on information technology

Emilsson speaking at the Cato Institute in 2011

Standardisation is key. As Per Ledin, who replaced Hultin as CEO in 2007, told the Economist: ‘If we’re religious about anything, it’s standardisation’. Odd Eiken, in a paper for the OECD, emphasises the point: ‘every step and element of learning is defined – from teachers’ roles to IT and architecture’. The aim is to create a low-cost, standardised, easily replicable service which can be sold in multiple markets: Sweden, England, the USA, and beyond.

Rupert Murdoch – who at the time still had millions invested in his own education technology business – was impressed enough to travel to Sweden to see what he called the ‘IKEA schools’.

Per Ledin, the new CEO, was happy to go a step further: ‘We do not mind being compared to McDonald’s’.

Economies of scale

The architecture is important. Kunskapsskolan’s schools are all built to a standard design. This design embodies a certain, rather Swedish, idea of modernity: large, open-plan spaces, a lot of glass and light, a certain functional bareness. As Odd Eiken puts it: ‘more like the site of a modern, creative knowledge industry […] than a traditional school’. The special design also involves significant economies. In traditional Swedish public schools, the average ratio of square meters to student is 12:1; in Kunskapsskolan’s schools, it is 7:1.

Rooms have to be used flexibly. Eiken again: ‘The laboratory also serves as a base group room, the cafeteria doubles up as a space suitable for collaboration or as a study area […] and all spaces in between rooms are learning spaces’. At Kunskapsskolan’s one US school, the Innovate Manhattan Charter School, there was no playground or gym; according to a schools review website, ‘students have physical education a few times a week in a room that doubles as a cafeteria’.

Inside Kunskapsskolan’s Innovate Manhattan Charter School, which opened in 2011 and closed four years later

Kunskapsskolan’s schools also have limited facilities for practical subjects. When the first five schools opened in Sweden in 2000, the company also set up a craft centre, to be shared by all the schools on a rotating basis. Students board at the centre for two weeks at a time and do woodwork and art projects.

‘We don’t want teachers preparing lessons’: the KED Program

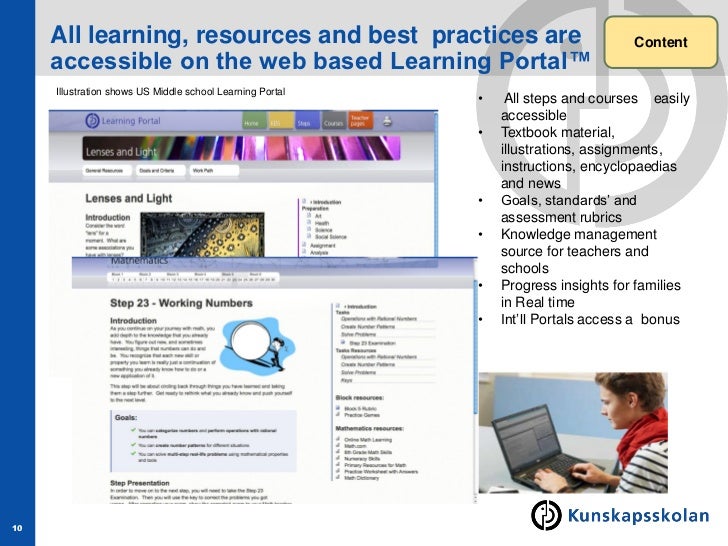

The most important feature of Kunskapsskolan’s model, however, is the use of information technology. The template for every school run by the company is the software known as the KED Program, ‘a complete tool box for coaching, web-based curriculum and learning material, manuals, design, performance management and administrative processes’. In other words, Kunskapsskolan uses IT to standardise most aspects of running a school – including the work of the teachers.

Students at Kunskapsskolan’s schools follow a totally standardised (and copyrighted) curriculum, accessed via the online Learning Portal™. Today, when mega-firms like Pearson and Google are busy developing online ‘learning management systems’, it is easy to overlook the fact that this small company from Sweden actually led the way. But Kunskapsskolan’s proprietary, web-based curriculum – which can be tweaked, obviously, to fit the requirements of national test regimes and accountability systems – is as innovative, in its way, as IKEA’s self-assembly furniture. And it has given rise to an educational model in which the position of the student is not unlike that of an IKEA customer, as we will see.

Teaching in all ‘KED schools’ must follow the script laid down by the Program. To quote Per Ledin again: ‘We tell our teachers it is more important to do things the same way than to do them well’. In fact, as Peje Emilsson told the Cato Institute, teachers are ‘not allowed’ to plan their own lessons. Ledin explains why:

We don’t want teachers preparing lessons during term-time. Instead we steal that preparation time, and use it so they can spend more time with students.

This is a very puzzling statement. Teaching is not a zero sum game, in which teachers can only carry out certain key responsibilities (supporting students) if they are relieved of others (planning and preparing lessons). Unless, of course, the aim is strict control of costs, especially wage costs, in order to generate a profit. As Odd Eiken told the OECD in 2011: ‘By consolidating back office processes and liberat[ing] teachers’ time from some common administrative and preparatory tasks, we have been able to “finance” the system’.

Personalised learning, or everything you ever wanted to know … in 40 steps

Every student at a ‘KED school’ is given a logbook, and invited to set themselves targets (e.g. to get an A in English). These form the basis of the student’s personal learning plan. Students meet their targets mainly by logging into the Learning Portal™, and working through units of instruction known as ‘steps’. In Kunskapsskolan’s English schools, five key subjects – English, maths, science, modern foreign languages and ICT – were each broken down into 40 steps. As Odd Eiken notes, a key principle of the Kunskapsskolan method, apart from standardisation, is to ‘set tasks and slice them into manageable and assessable chunks’ – which can then be delivered by computer.

Every week, students’ progress towards hitting their targets (i.e. the number of steps completed) is reviewed in a 15-minute one-to-one meeting with a teacher. This is why Kunskapsskolan describe their teachers as ‘personal coaches’ (according to a company website, the role of teachers in this system ‘transcends teaching’). Of course, there are other forms of contact with teachers too: lectures, workshops, and what Eiken calls ‘teacher-led communication sessions’. But much of the students’ time is spent in solitary work on laptops, in the open-plan ‘office landscape’ that is so central to the model.

This is one version of what has become known as ‘blended’ or ‘personalised’ learning: the combination of computer-based instruction with some face-to-face or ‘in person’ teaching. The model is catching on rapidly with US charter school chains. Here in England, as well as being used in Kunskapsskolan’s English schools, it has been trialled by at least one other academy chain.

Personalised learning has a number of attractions for school managers in search of ‘a more cost-efficient, effective school operation’ (Emilsson). Most importantly, it allows student-teacher ratios to be drastically increased.

In the USA, for example, Rocketship Education, a Silicon Valley-based charter chain which pioneered the use of computer-based instruction with kindergartners, was able — albeit briefly — to achieve a student-teacher ratio of 50:1 (see this report from 2014).

Kunskapsskolan claim that their schools have a student-teacher ratio of 20:1, but this is only part of the picture. According to Samuel Abrams’ recent book Education and the Commercial Mindset, while each teacher is responsible for reviewing the progress of 20 students in the weekly meetings, each subject teacher is responsible for around 60 students. Hence, presumably, the use of lectures and ‘teacher-led communication sessions’, rather than more conventional lessons.

‘Schools and teaching have not changed for 100 years’

As was to be expected, given their background in PR, Emilsson and his colleagues marketed Kunskapsskolan with great skill. They were the first to use the line which is now repeated ad nauseam by the cheerleaders of computer-based instruction: that public education as we know it is a ‘factory-style’, ‘one-size-fits-all’ system, which has remained virtually unchanged since the 19th century.

Here is a sample, from the Kunskapsskolan website:

The school as most of us know it was an invention of the late 19th century. […] Mass education for mass manufacturing. Today’s school should prepare for a different world.

Here is Odd Eiken:

All industrialised countries more or less run the factory model for schools. And we all share […] the problem of adapting a one-size-fits-all model to a society where demands and needs are more diversified

And here – to give just one example of the effectiveness of Kunskapsskolan’s messaging – is Rupert Murdoch again:

today’s classroom looks almost exactly the same as it did in the Victorian age: a teacher standing in front of a roomful of kids with only a textbook, a blackboard, and a piece of chalk

This ridiculous claim was of course repeated by Michael Gove, who in 2011 told the TES that ‘schools and teaching had not changed in 100 years’.

Two years later, he cut the tape on a new £16 million site for the Ipswich Academy, run by Kunskapsskolan’s English franchise, the Learning Schools Trust.

‘If we spend a lot of money, we should have some return’

Kunskapsskolan’s entry into the English school market had actually begun a few years earlier. In 2007, Andrew Adonis, the architect of New Labour’s academies programme, invited the company to sponsor two ‘city academies’ in south-west London, on a not-for-profit basis. Interviewed in 2009, Anders Hultin was still unhappy with the terms of the deal:

if we spend a lot of money and make a lot of investment we should have some return to at least cover our costs, but they got so nervous because they didn’t want to see any transactions between the trust and the company in Sweden

In 2008, Kunskapsskolan established a UK subsidiary, Kunskapsskolan International. The purpose of this company, according to documents filed at Companies House, was to provide services – ‘marketing, info, and consulting’ – to the English academies, and to ‘develop and license methods for conducting school business’.

The directors of Kunskapsskolan International were Peje Emilsson; his daughter Cecilia Carnefeldt, who had been Kunskapsskolan’s Director of Information; and Johan Rohss, a manager with Investor Growth Capital, an arm of Investor AB – another Swedish holding company which is a major backer of Kunskapsskolan. The only English member of the team was Steve Bolingbroke, who was recruited from a big IT firm, the RM Group.

In 2010, the Learning Schools Trust was established. Nine trustees are listed in the minutes of the first board meeting. Five of them had a close connection with Kunskapsskolan: Cecilia Carnefeldt, Steve Bolingbroke, Lars Fredrik Lindgren (Executive V.P.), Birgitta Ericson (Director of Education), and Per Unckel. Another trustee, Patricia Hamzahee, worked for Kreab Gavin Anderson. Beatrice Engstrom-Bondy had been a partner at Kreab, and was a senior adviser at Investor AB.

Per Ledin joined the Learning Schools Trust board later in 2010. He stepped down as a trustee two years later, when Carnefeldt replaced him as CEO of the parent company. Ledin’s place on the LST board was taken by Emilsson’s son Calle.

Clearly, there could be no conflict of interest here.

Ofsted crashes the party

Two Learning School Trust academies opened in September 2010: Twickenham Academy (formerly the Whitton School) and Hampton Academy. The Ipswich Academy (formerly Holywells High School) opened in March 2011. In late 2012, the trust acquired another school, the Elizabeth Woodville School in Milton Keynes.

Michael Gove opens the Ipswich Academy’s new site, November 2013

In the autumn of 2013, the Ipswich Academy moved into a new, £16 million building, which was opened by Michael Gove. But the school was already in trouble. Ofsted had visited in July, and graded it ‘Inadequate’. Teaching was ‘weak’. The students were ‘bored and restless’. According to the inspectors: ‘Although they are able to access the academy’s online learning portal at any time […] many do not take advantage of this facility’. A key recommendation was that teachers should have more scope to plan their own lessons:

In the core of good lessons seen, teachers plan flexibly, allowing for independent work that challenges students of all abilities. Behaviour is good because students are interested.

The Ipswich Academy was still ‘Inadequate’ when Ofsted visited again early in 2015. And, once again, the inspectors recommended that teachers be allowed to ‘plan lessons effectively to meet the needs of different groups of students’. The school was soon in special measures.

The Twickenham and Hampton schools were also inspected in 2013. Both were graded ‘Requires Improvement’. The management at the Hampton Academy seem to have decided at an early stage to scrap the workshops, or ‘teacher-led communication sessions’, in favour of more conventional lessons. The inspectors approved:

The academy has made the right decision to have fewer workshops […] Students make good progress when workshops are carefully structured with resources ready, clarity about what is to be done, and the teacher knowing which students need help. They make very limited progress when these features are absent.

Two years later, however, the Hampton Academy was still struggling. Twickenham Academy was visited again this April, and judged ‘Inadequate’. A key recommendation was that learning should be made ‘more purposeful, interesting, and enjoyable’. The Learning Schools Trust acknowledged that ‘it did not begin to develop a reliable understanding of the school until very recently’.

A survey of all six Ofsted reports reveals a clear pattern of comments, suggesting some of the limitations of ‘personalised learning’:

When lessons are dull, students are not involved in their learning. (Ipswich, July 2013)

Too many pupils find lessons uninteresting. (Twickenham, April 2016)

students […] are not confident at working by themselves (Twickenham, Nov 2013)

Students, both in the main academy and the sixth form, report that they would like more in-class support. (Hampton, June 2015)

There is not enough good teaching to address students’ needs (Hampton, July 2013)

Teachers do not have all the necessary skills or understanding to teach their subjects. (Ipswich, Jan 2015)

‘Kunskapsskolan is concentrating on other markets’: the end of the Learning Schools Trust

In March 2014, the Learning Schools Trust was barred from taking on new schools. The following year, the DfE removed Ipswich Academy from the trust’s control. The school was handed over to the Paradigm Trust (whose board was, until recently, led by a senior manager with a private equity firm). The Twickenham and Hampton schools will join the Richmond West Schools Trust in September.

Steve Bolingbroke became CEO of the Learning Schools Trust in 2013. He seems to have known that the writing was on the wall for Kunskapsskolan’s English franchise, telling Education Investor: ‘Until such time as the maintained schools sector [in England] is more suitable for investment, Kunskapsskolan is concentrating on investing in other markets around the world’. The company is developing chains of fee-paying private schools in India and the Middle East.

A student at one of Kunskapsskolan’s private schools in India

In June, Schools Week reported that Kunskapsskolan was finally exiting the English schools market.

US charter schools ‘go blended’

Failure to break into the English market was matched by a setback on the other side of the Atlantic. Kunskapsskolan’s Innovate Manhattan Charter School, opened in 2011 at the invitation of Joel Klein, NYC’s schools chancellor, closed just four years later.

But if Kunskapsskolan has dropped the baton in the US, the big charter school chains are rushing to pick it up. As one ed tech booster noted in 2013: ‘no-excuses charter networks across the United States are experimenting more and more with blended learning in various forms’. ‘Personalised learning’ is emerging as the next evolutionary phase of the ‘no excuses’ school model created by the KIPP chain, and so widely imitated both in the US and here. KIPP itself is currently ‘going blended’, with schools in Los Angeles, New Orleans and Chicago leading the way.

Kindergartners at KIPP Empower in Los Angeles, the chain’s first ‘blended’ school (image: Larry Abramson / NPR)

And Silicon Valley is very keen on personalised learning, which is turning charter schools into test-beds for the products of the ed tech industry — ‘learning management systems’, ‘learning analytics’, ‘AI personal tutors’, and all the rest of it.

‘This journey is just beginning’

At the end of last year, Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan launched the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative. This private investment vehicle — or, more precisely, limited liability company — is a stunning example of the new ‘venture philanthropy’, with $45 billion reportedly at its disposal. And the CZI looks set to funnel millions of those philanthropic dollars into education technology, and blended learning in particular. As Zuckerberg puts it, echoing Kunskapsskolan’s marketing material:

Technology in personalised learning enables teachers and students to create personal learning plans, track progress and find materials to help them learn best. When technology is tailored to students’ needs, it frees up time for teachers to do what they do best – mentor students.

In the Zuckerbergs’ touching open letter to their baby daughter Max, there is more of this kind of stuff — as well as the bizarre claim that computers and the internet, of all things, will ‘give all children a better education and more equal opportunity’. Or, at least, improve their test scores.

Our generation grew up in classrooms where we all learned the same things at the same pace regardless of our interests or needs. […] You’ll have technology that understands how you learn best and where you need to focus. […] Of course it will take more than technology to give everyone a fair start in life, but personalised learning can be one scalable way to give all children a better education and more equal opportunity.

We’re starting to build this technology now, and the results are already promising. Not only do students perform better on tests, but they gain the skills and confidence to learn anything they want. And this journey is just beginning.

Summit Public Schools

One of the early beneficiaries of the Zuckerbergs’ philanthropy was a California-based chain of charter schools, Summit Public Schools. The chain started out in 2003 with a version of KIPP’s boot camp culture, but then moved to a tech-based model very close to Kunskapsskolan’s.

Summit’s flagship ‘blended’ school, Summit Denali, opened in 2013. At the heart of the school is an open-plan ‘office landscape’ of the kind beloved by Odd Eiken: a bare, warehouse-like space, where dozens of children sit around working on laptops. Summit’s CEO, Dianne Tavenner, describes this as ‘an open architecture learning space’. The school seems to have no science labs, no library, no music or art rooms, no workshops, and no proper sports facilities. Students apparently go to a nearby public park to exercise.

(Image: Nichole Dobo / Hechinger Report)

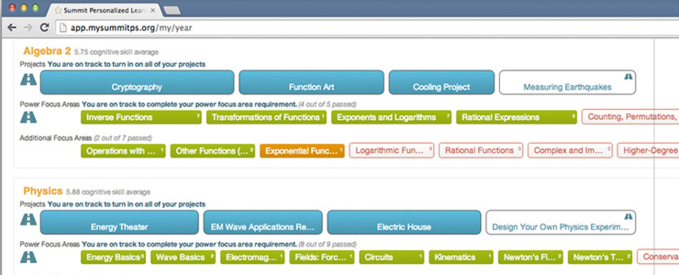

They are expected to spend at least 16 hours per week (eight in school, and eight outside) using computers to work through ‘Power Focus Areas’ in five core subjects, with each unit followed by a multiple-choice test. Data from the tests is relayed to, and analysed by, the teachers’ computers, allowing those in need of ‘support’ to be effectively targeted.

This work is interspersed with ‘rich, project-based learning experiences’, in order to develop ‘higher order thinking skills’. It is hard to get a sense of what exactly this ‘project-based learning’ consists of, given the very limited facilities at Summit schools – but it also seems to be mainly delivered by computer.

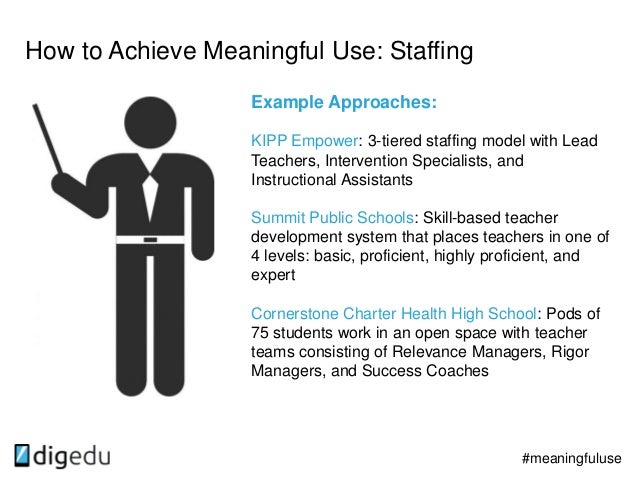

The Blended Human Capital Model

Another noteworthy feature of Summit’s operation is its ‘Blended Human Capital Model’, to use the words of an admiring report by the Dell Foundation. According to Dianne Tavenner, the chain is ‘redesigning teacher roles to move towards teams of educators, which can include teachers, learning coaches, intervention specialists and data analysts’.

‘Innovative staffing models’

Here Summit is following the example of the Rocketship chain of charter schools, where staff are divided into ‘master teachers’ – typically young Teach for America recruits, whose training consists of a five-week summer camp – and hourly-paid assistants (‘Individualised Learning Specialists’) without any kind of teaching qualifications, who supervise online instruction. As John Danner, Rocketship’s co-founder, points out: ‘You basically save 25 per cent of your staffing costs’.

Facebook does schools: the Personalised Learning Platform

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Summit Public Schools has received funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as well as the Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative. But Mark Zuckerberg has more than just his money to offer. In 2014, Facebook assigned a team of engineers to help Summit develop an online Personalised Learning Platform known as ‘Basecamp’.

The Facebook / Summit Personalised Learning Platform: ‘a sophisticated learning platform that serves up playlists of open content, helps students manage projects, tracks progress, and keeps students on schedule’

For those who might worry about the dividing line between the philanthropic goals of the CZI and the commercial interests of Facebook — well, such lines were wiped away long ago in the brave new world of venture philanthropy.

Chairman of the board

Summit Denali. The slogans on the wall — ‘Be Persistent’, ‘Strategy Shift’, ‘Respond Productively’ — refer to the ‘Habits of Success’ taught to Summit students (image: Nichole Dobo / Hechinger Report)

Who are the leaders of Summit Public Schools’ educational revolution? The board of directors of the California schools includes two venture capitalists, two investment fund managers, the CEO of a healthcare company (‘Proteus Digital Health’), a real estate broker, and a former CEO of eBay. None have any background in education.

The chairman of the board, Robert J. Oster, is a ‘private venture investor’. His profile at Oak Stream Partners LLC, a private equity search fund, gives a sense of the background to his interest in public education. He is or has been an investor in:

- Carillon Assisted Living, a private assisted living company

- Raptor Technology, a private school visitor management software company

- Pacific Pulmonary Services (now part of Teijin Holdings) an oxygen and medications company

- Industrial Water Treatment Services, a private industrial water treatment and services company

He is also a partner with Spring Ridge Ventures, ‘a venture capital partnership focusing on technology in healthcare’.

Finally, it is perhaps worth noting that, of Summit’s forty-strong management team, seventeen people are dedicated to ‘information’ or ‘communications’.

Marketing material from Summit Public Schools

So much for Silicon Valley. Here in England, the collapse of the Learning Schools Trust may slow the spread of ‘personalised learning’ into state-funded schools — for the time being, anyway. But the fact is that other, bigger academy chains — United Learning, for example, or the David Ross Education Trust — are already experimenting with computer-based instruction.

And the use of ed tech to ‘improve cost efficiency through both staffing and school design efficiencies [sic]’ is being driven forward by one particularly influential chain, whose board of trustees bears comparison with Summit’s. This, of course, is Ark Schools. Their Pioneer Academy – initially called the Blended Learning Academy – is scheduled to open next September.